“O PIONEER!” ARTFORUM Feature

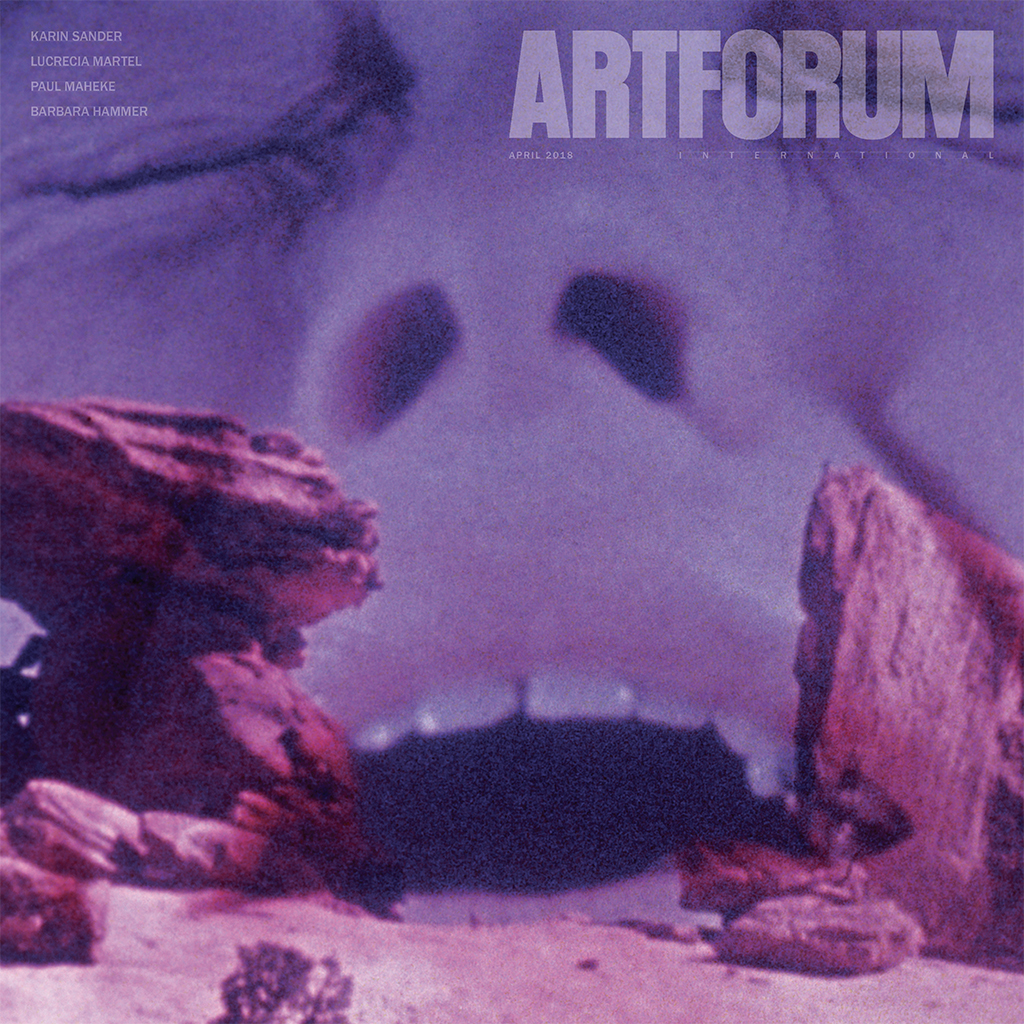

ARTFORUM Print April 2018

TWO THOUSAND SEVENTEEN was a milestone year for the irrepressible Barbara Hammer. In October, the seventy-eight-year-old pioneer of experimental queer cinema, who has produced almost ninety films over the course of her five-decade career, was the “first living lesbian” to receive a retrospective at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in New York. Titled “Evidentiary Bodies,” the exhibition was a testament to the singular combination of sincerity and irreverent humor that characterizes her sex-positive feminism. Featuring an impressive range of films and videos, early drawings, collages, and rarely seen installations, the show revealed how consistently Hammer has explored perception and pleasure, lesbian sexuality, queer invisibility, aging, and illness. In conjunction with the exhibition, Hammer screened newly restored prints of her 16-mm works at the New York Film Festival, Anthology Film Archives, Metrograph, and the Museum of the Moving Image.

In addition, her film and video collection was acquired for distribution last year by Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), and ten of her early films—including Menses, 1974; Superdyke, 1975; and Double Strength, 1978—were preserved by EAI and the Academy Film Archive through the National Film Preservation Foundation’s Avant-Garde Masters Grant program and the Film Foundation. She also exhibited photographs, many never shown before, in a solo show at Company Gallery in New York, and her vast paper archive was purchased by the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, where it will be housed alongside those of Georgia O’Keeffe, and Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. Hammer has also founded the Barbara Hammer Lesbian Experimental Filmmaking Grant, an annual award to be administered by Queer|Art. All this current attention—and the richly deserved accolades—demands the question: How can we make the most of, as she likes to call it, “Hammer Time”?

Although she’s long been a radical force, institutional recognition of her work has been slow in coming: The Museum of Modern Art in New York held a retrospective screening series in 2010, followed by another in 2012 at Tate Modern in London, but the very public embrace of Hammer in 2017 was on a scale finally in accord with her contributions. It called to mind a question Carolee Schneemann once pointedly asked about her own lack of art-world success: “Was I just a little too early? Or is it because my body of work explores a self-contained, self-defined, pleasured, female-identified erotic integration?” Like Schneemann, Hammer is a woman who uses her own body to create radically sexualized art. Critics, particularly poststructuralist critics of the 1980s, were quick to label Hammer’s work “essentialist,” arguing that her depictions of women-only groups communing naked in nature reduced female identity to the physical body and upheld the notion that the differences between men and women were biologically determined and genetically defined, as opposed to shaped by social constructions. Ironically, both Hammer and Schneemann, who recently received a fantastic but belated retrospective at MoMA PS1, are now widely lauded as cutting-edge feminists for the very work that was once dismissed as politically reductive.

While Hammer’s 16-mm films of the early 1970s were well received by her male professors at San Francisco State University, she frequently found herself in the position of being too experimental for lesbian audiences, and too focused on images of the female body for experimental-cinema audiences, particularly those steeped in the structuralist filmmaking that was dominant at the time. After creating a series of films exploring lesbian identity (Dyketactics, 1974; Superdyke; and Women I Love, 1976), Hammer focused increasingly on what she called “haptic cinema,” in which the representations of touch and the tactility of film are brought together to form a connection between sight and touch. In 1983, she left San Francisco for New York, so she could, as she wrote in her 2010 autobiography, Hammer! Making Movies out of Sex and Life, “meet my critics on their own turf, writers who found my films too soft, too ‘touchy-feely.’” Hammer, who often starred in her own work, now took herself out of the picture for Optic Nerve, 1985, a tender homage to her dying grandmother, and No No Nooky T.V., 1987, which documents the seductiveness of the then-brand-new Commodore Amiga computer and its digital-graphics program Deluxe Paint. But as the culture wars raged in the 1990s, she returned to the screen with Nitrate Kisses, 1992; Tender Fictions, 1995; and History Lessons, 2000, a trilogy of feature-length films on gay, lesbian, and queer identity that blurred the lines of documentary and essay.

Dyketactics was Hammer’s first major work, and in her estimation it is the “first lesbian-lovemaking film to be made by a lesbian.” In her autobiography, Hammer explains that she had intended to make a feature reflective of the “energies and dreams of a feminist revolution.” She shot a group of women (and a child or two) in the wooded countryside of Northern California as they traipsed in the nude through fallen leaves, washed one another’s hair, danced, and laughed. With over an hour’s worth of material, she retreated to the editing room only to discover it was boring: “I looked at the footage of the nature rituals and yawned.” She decided to trim to only those shots that captured moments of touching, since it was the experience of touching another woman’s body that had so fueled her desire.What remained were two minutes of images of women among the trees. But even these shots were, ultimately, mediated through the superimposition of others showing women driving, photographing themselves, and sniffing a vibrator—that is, at a conscious remove from nature. A minute and fifty seconds into the film, the images disappear into a field of red. The color wash interrupts the continuity and marks the transition from outdoors to indoors, and from focusing on a group of women to just a pair, as we move to part two. For this, Hammer asked cinematographer Cris Saxton to film her having sex with a friend. But as the film’s subjects became more and more intimate, the camerawoman was eliminated: Saxton placed the wound camera between the women’s bodies as they caressed, and stepped away. The result was a highly charged, highly emotive four-minute feat of erotic filmmaking.

Watching the film now, it is striking how unwarranted the critique of essentialism was. As Hammer was quick to point out, she never embraced the idea of a female essence, but she did feel an urgency to represent lesbian women. In a 1988 essay for Center Quarterly, she contested the essentialist claim: “Because we had represented lesbian women, the assumption that we inhabited these representations with biological, essential ‘meaningness’ separate from ideology or social construction was falsely made.” As film scholars Greg Youmans and John David Rhodes have argued in recent essays, there is always a performative element in these manifestations of lesbian identity. Rhodes identifies it in the “act of inscription” in the film’s title shot, as the camera captures the final letters of the word DYKETACTICS being painted on a concrete embankment; Youmans sees it in the playful performativity of the women in Superdyke, who conquer San Francisco by camera to “construct new queer worlds.” But even while recognizing how that identity is constructed, Hammer grounds the female experience in the body, and between bodies, for in her films one’s own body is almost always understood in connection with another woman: teacher, friend, or, most often, lover. Hammer embraces, even exploits, her personal relationships fearlessly, exposing herself without seeming to worry about the consequences.

Superdyke Meets Madame X, 1975, isn’t as well known as her 16-mm works of the same period, yet it’s key to much of her output. It has all the requisite elements of a Hammer production: a seemingly unlimited enthusiasm for exploring new bodies and new mediums; an earnest attempt to capture visually what it feels like to touch another woman; a confessional tone that characterizes the excitement of a burgeoning relationship and the disillusionment and boredom that can follow; and, above all, a radical openness and generosity with her collaborators on-screen—and with her audience. The film also reminds us, more explicitly than her others, how Hammer deliberately mediates the female body and provides a glimpse of her dynamic tangle of media, generations, discourses, and disappointments.

The premise of Superdyke Meets Madame X is simple enough: In the summer of 1975, video artist Max Almy taught Hammer how to use a Sony Porta-Pak, and she in turn taught Almy how to shoot in 16 mm. Their artistic relationship soon expanded into a sexual one. Over the course of the twenty-minute film, we see Hammer, a self-appointed delegate of analogue, investigate the medium of video, all the while sensuously studyingAlmy’s body with her lens. Hammer was initially thrilled by the immediacy of video as compared to film, and by its ability to record synced dialogue. Lounging on a bed, topless beneath denim overalls, she enthuses: “I’ve never . . . been able to record who they are as they’ve been telling me who they are.” But challenges soon arose. As one of the women explains via voice-over during a sex scene, “It looked really good, but we weren’t feeling.” The limitations of video—its immediate, narcissistic feedback, its glitches and breakups—reflected the limitations of Hammer and Almy’s relationship, and Hammer confessed a desire for a more direct connection with a larger public. At the end of Superdyke Meets Madame X, she stumbles on the idea for her next film. She will abandon video altogether, shooting a new project, Multiple Orgasm, 1976, in 16 mm, but Almy will stay in the picture a bit longer: In the new film, she tells stories to which Hammer masturbates to orgasm again and again.

Hammer’s work reminds us that visibility is a political act. She likes to get close, and, at times, this means showing naked bodies of all ages. Early in Superdyke Meets Madame X, for example, Hammer stands before the camera, naked save for a bandanna, headphones, and a necklace. “Everybody has seen me.” She laughs. “I’m not going to show my body again in film until I’m eighty!” More recently, she documented her own battle with ovarian cancer. At one tender moment, she overlays images of the IV bag that steadily drips chemicals into her with shots of herself wading naked into a river, her head bald and her steps tentative. Her willingness to show her body at its most vulnerable brings us closer than would seem comfortable, and yet it never diminishes her sensuality.

At other times, she draws us close simply by talking to the people around her. She is as relaxed with a microphone as she is with a camera in hand, and in her films dialogue is never stiff or strained; on the contrary, it is exuberant, confessional, immediate, sensual, fluid. After a screening at EAI last November, I was struck by how Hammer worked the crowd with the skill of a natural performer. She took some questions, answered them thoughtfully and honestly, and then approached a member of the audience. “What are you thinking about?” she asked with a broad smile, gently holding the microphone up to the surprised woman’s face. Asking a viewer how the film made her feel was a simple but radical gesture that upended the hierarchy of guest and audience. The effect of the gesture now, when communication can feel so loaded, when we are experiencing a collective outpouring of personal stories but also seem uncertain about what is and is not acceptable to say, is liberating.

The disarming sincerity with which Hammer attended to her audience comes from a utopianism in her approach to artmaking. Her films urge us to break out of our cynicism and anger and risk naïveté, amateurism, disenchantment. In a 2010 interview with Cassandra Langer, Hammer described the pejorative label of essentialism as a “real attempt to silence a lot of us.” She went on to say, “Luckily, it didn’t stop me. But I was hurt by it—all of us were hurt by the sweeping authoritarianism of the criticism. . . . We are leaving documents and ground to stand on for a younger generation, so when people get discouraged they can look to us for encouragement, to go on fighting as we have and still are.” Hammer has consistently pursued intergenerational dialogues in her work. She chose emerging curators Staci Bu Shea and Carmel Curtis to organize her Leslie-Lohman retrospective, for example, because she wanted to have a new generation’s take, and she often collaborates with younger filmmakers such as Gina Carducci. She created her lesbian experimental filmmaking grant because “working as a lesbian filmmaker in the ’70s wasn’t easy . . . and I want to make it easier for lesbians of today”; its first recipient, Los Angeles artist Fair Brane, was announced in December. The recent attention given to Hammer’s work not only reminds us of her profound presence in art and film history but also insists on the political urgency of representation—an urgency that the current climate has made all too clear.As we continue to fight for the rights to our bodies and ourselves, we would do well to consider how we might play on Hammer’s ground, and how we can continue to build on it.

Rachel Churner is a New York-based art critic and a founder of No Place Press.